Sometimes you can’t help but to look at two different steaks and wonder why one is 3 times more expensive than the other. We have lots of options as steak lovers. Each with their own pros and cons. Here are a few tips to help decide which steak is best for you.

There are many factors that affect how much a steak costs. The cut of steak, the type of feed the animal ate and even the breed of the cow itself.

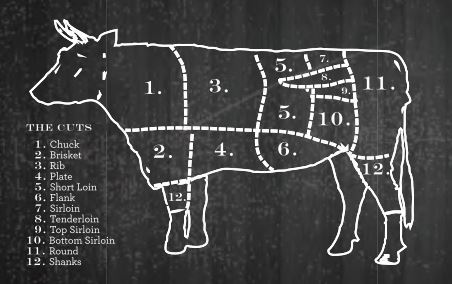

Each of these steak cuts come from a particular muscle in the animal, the filet from the tenderloin (which runs through the hindquarter of the animal and through the short loin and sirloin cuts), the ribeye from the rib section and the strip from the short loin. The Porterhouse and T-bone come from here as well but we will cover those later. And finally, the sirloin from the sirloin.

These selections all make ideal steak choices for one important reason – tenderness. Muscles that get used more frequently tend to be tough. That is why you don’t often see steaks from the round (rear leg) section thrown on the grill. They taste great, but you will be chewing for a long time. In order of tenderness the steaks above go as follows, filet mignon (from the tenderloin, tender-loin, get it?) ribeye, strip and sirloin.

There is a direct correlation between how tender a steak is and how much it costs. Other cuts you might see are flank or chuck . But these won’t be as tender if cooked using traditional methods.

Another thing to keep in mind is that muscles that are used more frequently, and are therefore not as tender, also happen to have a more robust flavor. This has to do with more blood circulation through the muscle while the animal is alive.

There is nothing that compares to the soft, velvety mouth-feel of a filet, but more than a few steak enthusiasts lament its subtle beef flavor and prefer a ribeye or strip steak because it offers more of that classic beef taste. Ribeye and strip steaks tend to give you the best balance in terms of cost, flavor and tenderness.

So now you know where the steaks come from, but what about all those words advertisers stick to them like Angus or Prime? All meat is inspected by the USDA for wholesomeness. This means if it is sold, it is legally fit for human consumption. Unfortunately, that is a pretty low bar, so the USDA has a grading system.

Grading is a voluntary system that beef producers allow their meats to be graded on in several categories. The long and short of it is a delicate balance of fat to lean meat, plus the age of the animal.

The younger the animal and the higher the fat marbling of the meat, the higher (and therefore more expensive) the grade. The only grades you want to consider, (even though there are eight of them, the bottom few named “canner” and “cull” – yum, right?) are prime and choice.

USDA Prime

USDA Prime

Prime can be expensive, but has beautiful fat marbling for a very tender steak.

USDA Choice

USDA Choice

Choice offers a great value of marbling and tenderness at a fair price.

But, remember, you only want to go with the most tender cuts. Certain breeders of cattle specialize in one breed, like Angus, Black Angus or Wagyu (this is a breed of cow from Kobe, Japan, where the animals have beer with their breakfast and at a minimum one hour of massage a day). These breeder associations have created their own system to market their cows with their own standards, not just the USDA’s.

Another component to look for is aging. When an animal is butchered the muscles become tough, but over time the muscles soften.

Freshly butchered meat is tough and chewy. The muscles need to relax before you try cooking them. A reputable supplier only sells meat that has been aged properly. There are two ways to age: dry and wet.

Dry aging is more expensive and often difficult to find. The meat is hung in a temperature and humidity controlled environment and allowed to rest for a set period of time. Eleven days or so has proven to be the magic number here where tenderness no longer increases. One of the reasons dry aging is more expensive is that you have considerable moisture loss and therefore a higher cost per pound.

Wet aging occurs when meat is packed into vacuum-sealed packaging and allowed to rest in its own liquid. Many consumers prefer wet aging because dry aging sometimes imparts a musty, basementy aroma.

So now you know what cut to look for and what grade you want. So where do you go? You should look for a butcher like you do a mechanic. A good one is hard to find. Once you find one, ask questions like, “Where do they get their beef from?” “Is it grain fed?” “How is their meat aged?”

A good butcher will answer all of these questions. Shop around and go to Web sites for information. There is plenty out there.

Hopefully this gives you some food for thought!